Chapter 1: Intro

An IPO is the first time that a company offers shares (or ‘floats’) to the public on a stock exchange.

It stands for ‘Initial Public Offering’, but you’ll often see it short-handed to ‘going public’ which has the same meaning.

Which exchanges are we talking about? They could include the London Stock Exchange, the New York Stock, Euronext, or the Hong Kong or Shanghai Stock Exchanges (and there are many others). But unless it’s a large business, it will likely be an exchange that specialises in smaller companies like London’s Investment Market (AIM) for example.

Chapter 2: Why IPO?

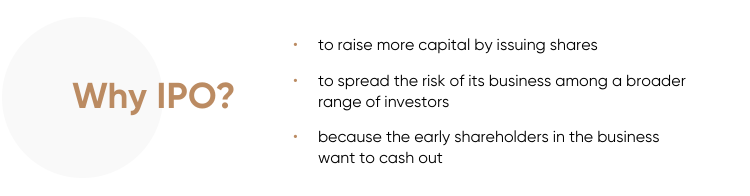

There are many reasons. The big one is simply to raise more capital by issuing shares to the public. Usually that’s to fuel expansion – either through building its existing business or acquiring others.

But there are other reasons. One is to spread the risk of its business among a broader range of investors, beyond its founders or initial backers.

Another could be because the early shareholders in the business want to cash out. Say a private equity company has invested in a business but now wants to cash in its investment; it can do so through an IPO. It’s a neat way to exit the business.

Chapter 3: How do you manage an IPO?

A company that is planning an IPO will often start preparing for it many months – and sometimes years – in advance. That’s because it’ll need to ensure its accounts, management and internal procedures will comply with the rules of the stock exchange on which it will be listed.

Advised by a stockbroker, securities company or investment bank that specialises in and is authorised to carry out flotations, the company and its advisors will first prepare a sales document or ‘prospectus’. This will set out all of the details of the company and is the IPO sales document.

The company then announces its intention to list in newspapers or on the web and through its advisers. Often those offered the shares will be institutions such as pension funds, insurance companies and investment funds.

They and investment banks may also underwrite the shares – which means they agree to buy the shares back if they fail to sell during the IPO process. Its advisors will look to pitch the shares at a price at which they will be sure to sell, so that the underwriters will not have to buy them in. But they sometimes get it wrong.

Chapter 4: What happens next?

Life isn’t the same again. After an IPO, the company lists its shares on its chosen exchange. This means it will also need to accept a higher level of public scrutiny and media interest – for better or worse!

If it is successful, the shares will increase in value – and all the shareholders will make a capital gain. These often include the company’s management and initial founders – and sometimes staff as well, if they’ve also bought or been given shares at the time of the IPO.

It doesn’t always go well. Sometimes the price falls. And sometimes, particularly with small companies, its investors show no great interest in buying and selling the shares – which are then said to be ‘illiquid’. That’s a risk that every business has to take if it goes public.

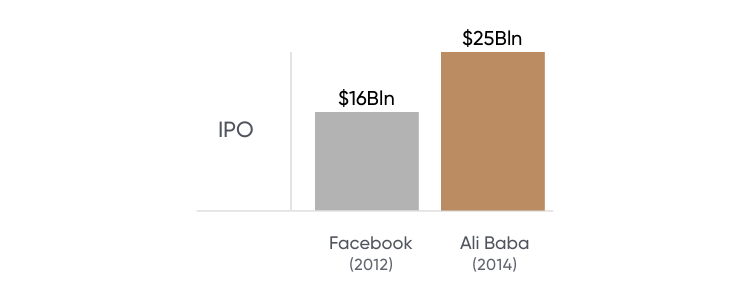

By the way, just in case you think that only small companies make IPOs, here are some big numbers to consider: in 2014 the Chinese web shopping and services Ali Baba Group carried out the largest IPO of all time. It raised $25 billion. This dwarfed even Facebook, which came to market in 2012 and raised $16 billion.